Are you wondering how to incubate chameleon eggs? One of the most rewarding experiences you can have as a reptile hobbyist is the successful hatching of an egg clutch. If you need help or suggestions as far as breeding goes, we have a very in depth blog article all about breeding Panther chameleons. But, for the purposes of this article, we’ll assume you’ve already got a clutch or two of your own incubating and we’ll focus specifically on what to do once your eggs are starting to hatch.

At Backwater Reptiles, we incubate our eggs in shoebox sized plastic boxes. We don’t drill any holes or provide any special means of ventilation (they don’t get much air circulation in nature being buried 6-12 inches underground).

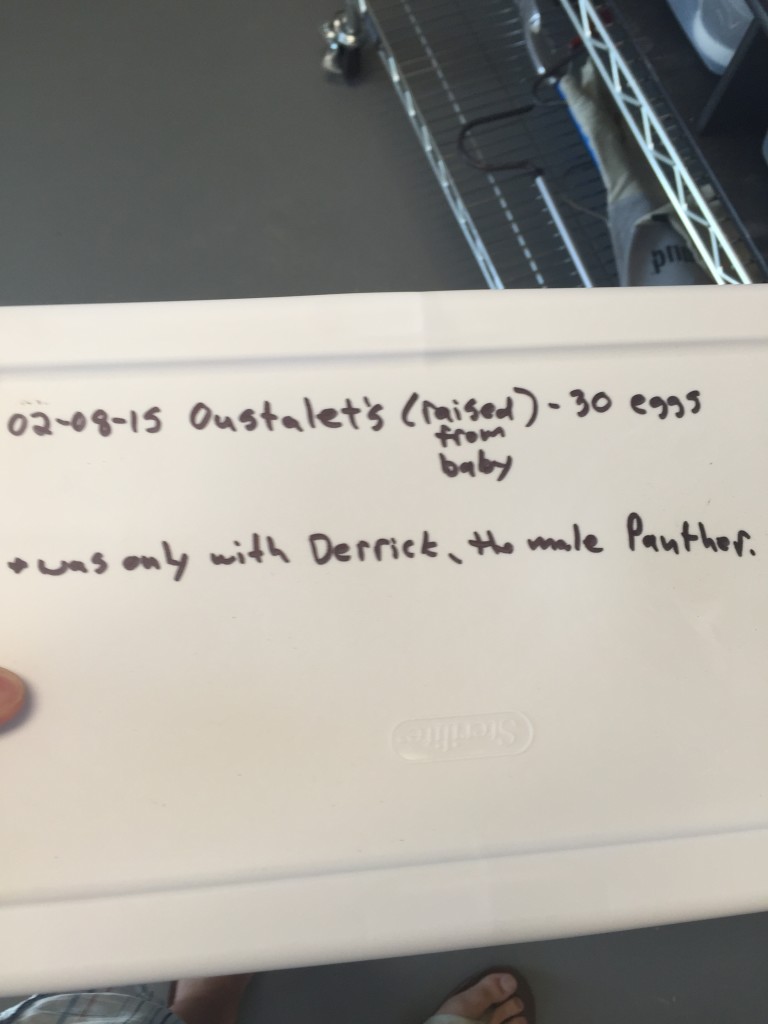

You can purchase these types of plastic boxes at any large department store. We fill the boxes with Perlite that is damp but certainly not dripping wet, label the boxes with the clutch date, close the lid, and store on a shelf at room temperature.

We’ve learned that the natural rise-and-fall of indoor temperatures provides the perfect environment for 90% of chameleons. We’ve hatched-out over 18 different species, and the only one that we don’t get strong hatch percentages with is the Carpet chameleon (Furcifer lateralis). We generally experience 100% hatch rates for Panther, Veiled, Sailfin, Flapneck, Oustelet’s, Pygmy, Verrucosus, Johnston’s, Two-horned, et al.

Many hobbyists purchase small pre-made incubators for their chameleon eggs, but we’ve found they are unstable and can experience sudden wide temperature fluctuations. If you take nothing else away from this article, remember this: quick temperature fluctuations are dangerous–very slow, gradual changes are far less so.

Chameleon Eggs: Part Deux

The amount of time it takes for the eggs to hatch varies based on the chameleon species, but for the purposes of this article, we’re using a clutch of Sailfin (Trioceros cristatus) babies that we had hatch this week (our fourth clutch). This particular clutch was laid on March 3rd, and took a little over six months to hatch.

Once you notice a single baby in the Perlite, it’s best to keep it in the box for a while as the eggs seem to “communicate” and incite the rest of the eggs to hatch. Some scientists believe there is some type of chemical communication involved.

You’ll notice that your hatchlings are very timid, weak, and clumsy. This is all normal! Just like human babies, hatchling chameleons of any species, not just the Sailfins pictured, need to learn how to use their limbs.

The babies will climb all over each other, use each other as stepping stools, and be generally awkward and bumbling for a few days. They might even curl up in little balls and appear for all intents and purposes to be dead, but it’s just the shock of the new world. Eventually they will snap out of it.

Once all of your eggs have hatched, it’s safe to move the babies to a separate home. We house our babies of a single species all together in small versions of adult cages. Keep the plant life and climbing materials in their cages minimal so that you don’t lose the little guys as they are very small! It’s also wise that your cage not be too tall as they stumble and fall often when they’re babies. Just like toddlers learning to walk, they have accidents and can fall off the plants/climbing materials and if you don’t want them to injure themselves, it’s best if they don’t have too far to fall.

They also need to be able to spot prey insects, and the more clutter you have in the enclosure, the more difficult it is for them. We usually affix a plastic plant to the top of the screen cage (near the UVB lighting–we use ReptiSun 5.0 bulbs), because the baby chameleons like soaking up the rays, and if you don’t provide a way for them to get off the top of the cage (by way of easily accessible leaves), sometimes they seem to be confused as to how to maneuver elsewhere.

We feed our hatchlings hydei fruit flies and pinhead crickets at birth once or twice a day. As they grow just a bit, you can increase the size of the prey items accordingly.

Baby chameleons need humidity, and plenty of it. Dessication (dehydrating) is their biggest enemy, and it’s an ever present threat. Mist, mist, and mist again. We have our’s set up with an automatic misting system, so that we don’t even have to think about it.

We hope you’ve enjoyed our article on how to incubate chameleon eggs! The Sailfin chameleon hatchlings from this post should be large enough to be shipped to new homes within about three months. They’re a wonderful species with a unique appearance, and they generally thrive in captivity, especially when you start with captive bred babies.