It goes without saying that every member of the Backwater Reptiles team is passionate about reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates. But did you know that we often fall in love with the critters that come to our facility? In fact, the Backwater Reptiles office is filled with the pets of Backwater Reptiles employees!

Want to meet the herps and inverts that we love and live with at the office? Read on to learn more!

Meet the Resident Reptiles, Amphibians, and Invertebrates of Backwater Reptiles

Nyke – Anerythristic Savannah Monitor (Varanus exanthematicus)

If there were a single reptile that is the face or mascot of Backwater Reptiles, it would be Nyke.

Nyke is approximately three years old and he was the first pet reptile adopted by an employee. He arrived at the facility as a tiny little anerythristic Savannah Monitor and he has grown into quite the beast with an appetite to match.

Nyke started out in a small terrarium eating small insects such as crickets, mealworms, roaches, and other similar invertebrates. Now, at his current size, he’s eating a varied diet of mice, eggs, and other animal proteins.

Check out the video of Nyke eating some quail eggs below.

Friendly as a lap dog, Nyke is known for roaming the office and begging the Backwater Employees for scraps, even if nobody is eating! He enjoys sitting on our laps, getting scratches on his head and chin, and staying warm and cozy under his heat lamp.

Savannah Monitors make excellent pets for reptile hobbyists who want an interactive animal. Not only do they take well to human interaction and provide endless entertainment at meal time, they are also known for their ability to adapt to leash walks and for taking baths in human bath tubs when they grow up.

If you are interested in a pet Savannah Monitor of your own, Backwater Reptiles has them for sale, however please do your research and be prepared to keep a somewhat demanding animal. Not only do monitors of all types require lots of food, they grow to large sizes and will need a space big enough to comfortably house them.

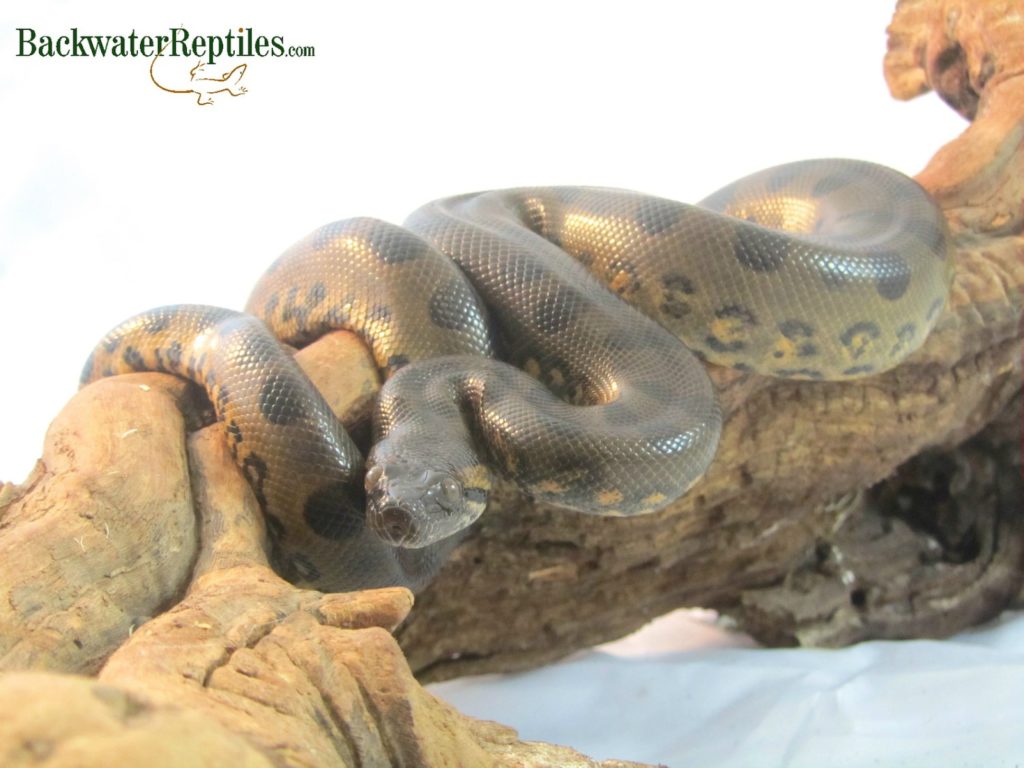

Vossena – Hypo Motley Colombian Redtail Boa (Boa c. imperator)

Vossena, a female Hypo Motley Colombian Redtail Boa, has been a fixture in the Backwater Reptiles office for quite some time. She came to us a little bit older than a hatchling, and she has most certainly grown!

Although she’s not the cuddliest boa at the facility, Vossena does spend plenty of time outside of her cage during business hours, interacting with the team while they work.

Vossena can get a bit nippy when she’s hungry, so we always make sure she’s well-fed before handling her and we exercise caution when removing her from her cage.

Zedsly – Colombian Redtail Boa Mix (Boa c. imperator)

Zedsly came to the Backwater Reptiles facility as a rescue — and the team fell in love with him! We’re not one hundred percent sure, but he is a Colombian Redtail Boa mix with probable Hypo genes.

Zedsly is also the newest reptilian family member to join the Backwater Reptiles crew. He spends most of his time chilling out in his cage next to his mom’s computer work station, but like all the other resident office snakes, he enjoys spending time with the employees while they work.

Colombian Redtail Boas are very popular amongst reptile enthusiasts with good reason. They are adorable as hatchlings and they mature into decent-sized snakes that tend to enjoy being handled. If you are interested in a Colombian Redtail Boa of your own, you can purchase one from Backwater Reptiles here.

DeVille and Tartar – Crested Geckos (Rhacodactylus ciliatus)

This Crested Gecko duo are actually related! Tartar, who got his name because his coloration resembles the condiment tartar sauce, is DeVille’s son!

Little Tartar was actually hatched at the Backwater Reptiles facility last year. DeVille, on the other hand, came from a reptile show. Despite the fact that we handle reptiles and other critters on a daily basis, we are still susceptible to their charms and we rarely go to a show without taking a new family member home.

Overall, the geckos mostly keep to themselves. They enjoy meal time and hiding in the foliage in their cages.

If you are interested in a pet Crested Gecko of your own, you can purchase adults, babies, and various morphs here.

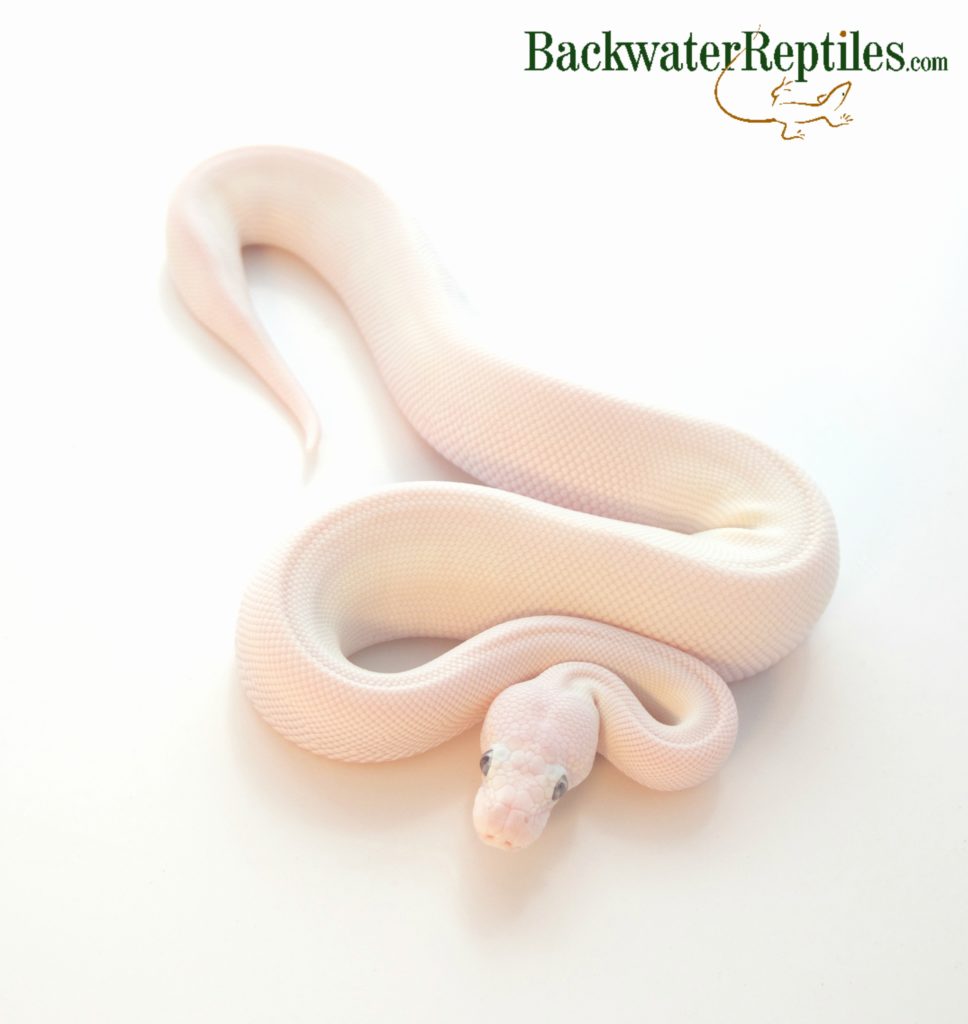

Hades – Blue Eyed Leucistic Ball Python (Python regius)

Hades is a blue eyed leucistic Ball Python around a year or so old. He arrived at the facility as a hatchling and has since undergone multiple sheds and grown appropriately.

If you were to visit the Backwater Reptiles facility, you’d likely find Hades sitting in his mother’s lap if she’s at the computer. He enjoys the warmth and helping out with sending emails.

While Ball Pythons can be stubborn or picky eaters at times, Hades has always had a healthy appetite. He’s grown from eating pinkie mice to frozen/thawed fuzzies. Sometimes he’ll even eat two in a row!

Overall, Ball Pythons are great pet reptiles for hobbyists of all experience levels. They aren’t very hard to maintain and their housing requirements are fairly simple. They are popular additions to reptile collections because they are available in a seemingly endless variety of color morphs.

If you are interested in owning a pet Ball Python of your own, Backwater Reptiles has quite a collection of morphs available for sale. We can also acquire rarer morphs – just email our customer support team at sales@backwaterreptiles.com if you are interested in a morph not listed on our website.

Franklin – White’s Tree Frog (Litoria caerulea)

Franklin the Dumpy Frog is a recent acquisition to the Backwater Reptiles critter family. He arrived at the facility last year and has been charming us with his cuteness ever since.

On any given day, Franklin can be found hanging out in the foliage or on the walls of his enclosure. He’s known for being very photogenic as he appears to be smiling in just about every photo he takes.

Franklin enjoys eating crickets and other insects and having his enclosure misted.

Whites Tree Frogs are very hardy pet amphibians and we do highly recommend them for beginners. Like most pet frogs, they should be handled sparingly, but overall they are a friendly species.

If you’re interested in a Whites Tree Frog of your very own, Backwater Reptiles sells them here.

Manson – Antilles Pink Toe Tarantula (Avicularia versicolor)

Manson is an Antilles Pink Toe Tarantula about a year to a year and a half old. He arrived at the facility as a tiny spiderling with a half inch leg span and has grown into a colorful spider with a friendly disposition.

Manson has matured from consuming pinhead crickets to full-sized roaches and crickets. He’s got a healthy appetite and watching him at meal time is always a treat.

Although Manson doesn’t enjoy helping the team out with emails around the office, he does sit in his enclosure near the computers where he can oversee the Backwater Team comfortably.

Manson’s mom does handle him when he’s not preparing to molt and when he comes out of his hiding place or web to say hello.

Conclusion

Everyone working at the Backwater Reptiles facility loves reptiles, amphibians, and invertebrates.

So it’s no surprise that our office is filled with herps that make us smile and make the work day breeze by.

You can be sure that we’ll likely fall in love with more critters as they arrive at the facility. Guess it’s true for the Backwater Reptiles employees that reptiles are kind of like potato chips – you can’t have just one…even at work!