Do Gila Monsters make good pets?

Although they are fascinating animals as well as quite beautiful to look at, the truth is that Gila Monsters are not good pets. In addition to being venomous, these lizards are also very secretive and do not enjoy human interaction or being kept in a small enclosure in captivity.

Gila Monsters are not common pets and with good reason. They are actually illegal to own in many states, including California and Nevada. However, just because you can’t keep a Gila Monster as a pet doesn’t mean that they aren’t incredible creatures worth learning more about.

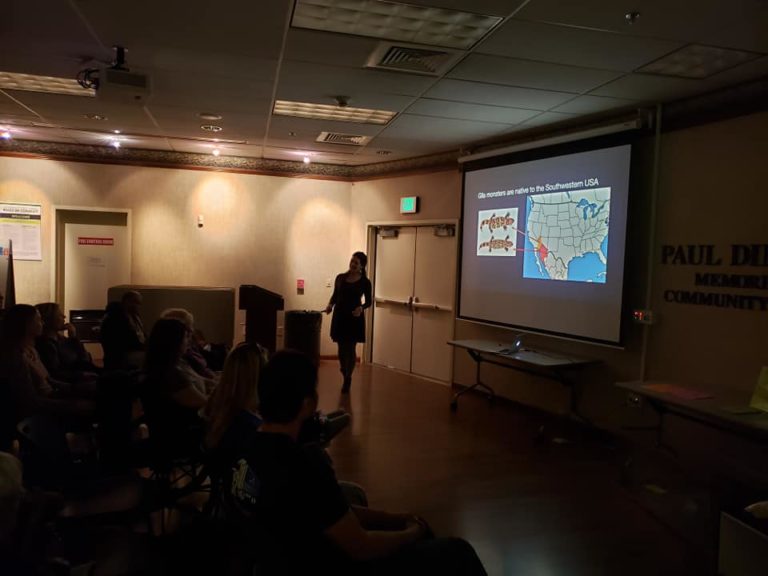

Backwater Reptiles is headquartered in Northern California and as such, we have the opportunity to attend the monthly meetings of the Northern California Herpetological Society. This month’s meeting revolved around the Gila Monster and a recent study of the population that exists within a specific region of Arizona.

What is the Northern California Herpetological Society?

The NCHS is a non-profit organization that revolves around reptiles and amphibians. They promote conservation, education and rehabilitation of herps and are just as enthusiastic about these wonderful animals as we are.

We were actually lucky enough to pick the brain of NCHS’s program director, Darlene Collisson. She was happy to answer our questions and speak about the NCHS and its goals. Continue reading to see what Collisson had to say.

Backwater Reptiles: This month’s talk is about Gila Monsters. What are your thoughts on keeping them as pets?

Darlene Collisson: I would not recommend Gila Monsters as pets due to the fact that their bites are venomous and that they live mostly in hiding and underground.

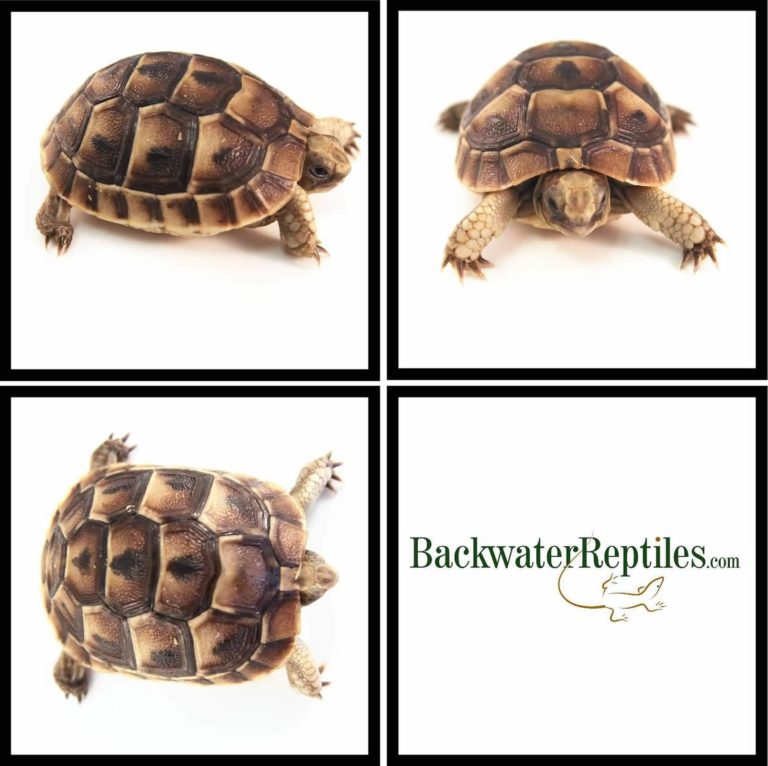

BR: Which herps do you feel make the best pets?

Collisson: There are many reptiles that make great pets. It just depends what you like, your level of experience and your willingness to provide the essential care they require. I don’t believe any can be classified as “easy pets” and the best is your own personal liking and your ability to provide the care it requires. I personally am partial to bearded dragons, corn snakes, kingsnakes, crested geckos, gargoyle geckos, and leopard geckos to name a few. I have a wide assortment of close to 100 reptiles in my little zoo.

BR: What do you think people should know about keeping reptiles and amphibians in captivity?

Collisson: Their care takes time and dedication. They are 100% dependent on you to provide the care they need to survive and thrive. They need to be provided with proper husbandry including diet, proper lighting and keeping their enclosure clean. Veterinary care is crucial and regular check ups are very important. Make sure to know of reptile (exotic) vets in your area before you have an emergency situation. Veterinary care can be costly, so it is very important to have money set aside when the need arises.

BR: What do you think of Northern California’s “reptile scene?” Do we have a

lot of breeders, hobbyists and enthusiasts in our area?

Collisson: We have an excellent reptile scene. I have encountered many knowledgeable breeders and enthusiasts in my years of keeping reptiles. We also have some great reptile stores in the area – GX3 Reptiles and Exotics, Reptile Depot and the Serpentarium to name a few.

BR: How does NCHS help rehabilitate herps?

Collisson: NCHS has a group of dedicated volunteers who provide foster care for reptiles that have been relinquished to us. These volunteers make sure that the reptiles are seen by a veterinarian ASAP to get a health check up and medical treatment if necessary. Once the reptile is deemed healthy, it is then placed as “available for adoption” on our website and Facebook page.

BR: What should the average person do if they discover a reptile or amphibian

in need?

Collisson: If discovered in the wild, leave them be and contact a local animal control or state agency. If in captivity, they can contact a local veterinary office or contact NCHS through our Facebook page or through “contact us” on our website.

BR:

Aside from the monthly meetings, what types of events does NCHS

participate in?

Collisson: Our big event of the year is the Sacramento Reptile Show usually held at the end of September. We also provide education & outreach to several local elementary school events along with other local community events. Were also get requests to come to individual schools/classrooms to share our reptile passion and provide “hands on” experience. We also attend adoption events at Petfood Express in Davis.

BR: How can people help out the NCHS?

Collisson: NCHS is a registered 501(c)(3) organization and relies 100% on donations to support our mission and to provide veterinary treatment for the reptiles in our care. We accept monetary donations or reptile/amphibian supplies. You can make a donation payment on our website or if you have an Amazon account you can link your account to Amazon Smile and select Northern California Herpetological Society as your charity of choice. NCHS then will receive a percentage of your purchases. At this time the amount is 0.5%.

BR: Do you have any final thoughts or comments about this month’s meeting, the NCHS or reptiles/amphibians in general that you wish to share?

Collisson: The Northern California Herpetological Society was established in 1982 and is a non-profit organization devoted to providing reptile and amphibian education, informing the public about conservation, and aiding in rescue and rehabilitation of captive species. NCHS is dedicated to providing information and increasing public knowledge about the proper care and husbandry of reptiles and amphibians in captivity. We strive to achieve this goal through our educational monthly meetings and community outreach events. Monthly meetings are free, open to the public, and hosted for those interested in herpetology!

March Meeting of the Northern California Herpetological Society

The NCHS meets on a monthly basis and each meeting typically features a guest speaker. This month’s meeting featured Victoria Farrar, a PhD grad student in the animal behavior program at UC Davis. Farrar participated in a study at the University of Arizona where she was able to monitor local gila monster populations within a state park.

Farrar’s study captured and kept data on gila monsters in order to determine how the local population was doing. The study’s goal was to determine if gene flow within the population was healthy and ultimately determine whether or not the park was beneficial to the lizards.

Farrar’s work had her getting hands on with gila monsters in the wild. She and her team had to capture the lizards and implant microchips for obtaining data on the animals. Farrar underwent rigorous training with the venomous lizards prior to being given permission to handle the animals.

The end result of the gila monster study was a positive one. It was determined that gene flow and population statistics were both healthy. Overall the state park was indeed beneficial and helpful in conserving and protecting gila monster populations.

One on One Interview with Victoria Farrar

Although we do work with many types of exotic reptiles, amphibians and invertebrates on a daily basis at Backwater Reptiles, we don’t have gila monsters on hand at the facility. So you better believe we were very curious about these cool critters. Luckily for us, Victoria Farrar was kind enough to take time to answer our questions in the form of a on on one interview, which you can read below.

Backwater Reptiles: Where did your interest in herpetology come from?

Victoria Farrar: I grew up in Arizona, and I saw a lot of herps, even in my backyard, mainly fence lizards. Reptiles were just always present in my life. Mmy mom had pet turtles, so I’ve always been around them as pets as well. I love the desert and you see a lot of reptiles out there in the desert and I’ve always just thought they were so special and cool. I heard about Dr. Bonine doing the research with the gila monsters and I thought that was way too cool of an opportunity to pass up. I wanted to get in on that. So I just reached out to him and he happened to have an opening.

BR: Did you keep any reptiles as pets or do you keep any now?

Farrar: I don’t have any now, but I did when I had a wildlife permit back when I was working on this project. I did have a Sonoran Desert Toad as a pet, a big fat, Jabba the Hut kind of guy. But unfortunately, he died. But he was really cute and his name was Al, after the toad’s scientific name Bufo alvarius.

BR: Why did you choose to research gila monsters? What was the goal of the whole project?

Farrar: Gila monsters are really charismatic and people care about them. They show up on tourist post cards and stuff like that. So we wanted to see if protecting national park land from development and building would actually protect wildlife. Would it help conserve them? Would it protect their gene flow and their movements and make their lives better? And gila monsters were a really great place to start because we know that they’re threatened, we know that people care about them and we don’t know much about them at all in reality. So we learned about the animals themselves and we also learned about how the park is helping to protect them.

BR: Did the fact that gila monsters are venomous pose any issues for you or your team?

Farrar: We definitely had to get trained properly. There was a long period in which we weren’t allowed to work alone and we really had to learn how to handle them and show our superiors that we knew how to handle them well. But once we did all that, we learned that they’re not that scary. I think that surprises a lot of people. I’d honestly say that the scariest part of the work I did was being out alone off trail in the desert, especially during monsoon season because it can flood. So the lizards themselves were actually not problematic or scary.

BR: Do you think gila monsters make good pets?

Farrar: People should not keep them as pets. They do not make good pets. It’s actually illegal in California and it’s also illegal in Arizona. I don’t know about Utah and Nevada, but I feel strongly that they should not be a pet.

BR: Any final thoughts or comments you wish to share? Specific things you want people to know about the gila monster?

Farrar: They are super cool! They’re one of the only venomous lizards in the world, so they’re really unique from an evolutionary perspective and even from a general diversity perspective. I think they have a lot to teach us, so it’s worth looking more into the secrets of the gila monster.

Conclusion:

So what did we take away from the March meeting of the Northern California Herpetological Society?

While gila monsters are very beautiful creatures that are worth learning about, they do not make good pets. Not only are they venomous, but they also don’t really like coming out of hiding to interact with people.

Luckily, although more and more of their native habitat is being encroached upon by humans, the gila monster population within the protected state parks of Arizona is doing well. The animals are able to meet each other, mate and maintain gene flow.

We also had the opportunity to learn a bit more about the NCHS and its goals within the community. We are grateful that Northern California has an organization that promotes health and welfare of our favorite critters.

Finally, if you want to help out or learn more about the Northern California Herpetological Society, you can visit their Facebook page or donate through the organization’s website.